The Mariners and That Winning Feeling

The Mariners enjoyed their first winning season in 1991 and they did it in the most Mariners way possible.

The 2024 season has mercifully ended for the Seattle Mariners. And while I certainly have a lot to say about THAT, I’d rather focus on old stuff here. Specifically, the first time the Mariners had a winning season. 85 wins may be disappointing to the 2024 Mariners, but once upon a time that would have been an unimaginably successful season.

Today, we are traveling back to Friday October 4, 1991, when the Mariners made history by clinching a winning season for the first time in their 15-season history.

It was a long road to 1991. The Mariners had had nearly as many 90-loss seasons (7) as managers (8). They were on their third ownership group. Fans had spent a decade being told the Mariners were on the verge of leaving town, and for a city that had already lost the Seattle Pilots to Milwaukee, it was no idle threat.

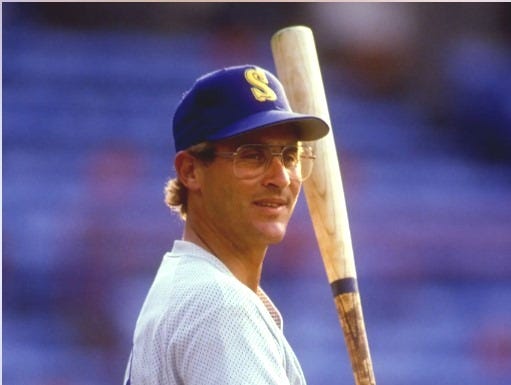

Still, there was a little hope glimmering in the distance as the 1991 season unfolded. Ken Griffey Jr. was in his third season in the major leagues, and even though he was only 21 it was clear he was going to be a star. Randy Johnson was becoming a dominant pitcher, although he was still wild. The year before he threw the first no-hitter in Mariners history. And we didn’t know it then, but the roster had players like Jay Buhner and Edgar Martinez who would become beloved all-time Mariners in a just a few more years.

Still, there was that hurdle to clear: the first winning season. It was a mark that every expansion team saw as the turning point; no longer a newbie team, now an established team. According to Britannica, the Mariners hold the record for the longest period before the first winning season with 14 losing years.1 I haven’t verified this, but it certainly feels like it’s correct.

By 1991 the Mariners were drawing comparisons to the 1933-1948 Philadelphia Phillies, the team that set the record for the most consecutive losing seasons with 16. Nobody wanted to add that mark of ignominy to the team’s long list of nonachievements.

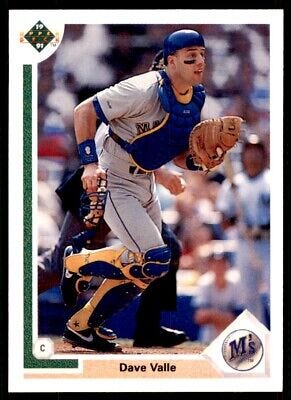

The 1991 Mariners clinched a .500 season with a 4-3 win over the Rangers in Texas on October 2. The achievement was met with a huge sigh of relief. After 14 losing seasons, the streak came to an end when Dave Valle doubled in Jay Buhner and Omar Vizquel to put the Mariners in the lead in the top of the 7th inning.

Losers no more, they weren’t quite winners yet.

“To beat that curse, we need to win a couple more,” said Alvin Davis. Davis was the Mariners’ longest tenured player, having broken into the majors in 1984 and winning the Rookie of the Year award. Randy Johnson agreed. “I see people jumping up and down here for a .500 record, but we still need to finish over .500…The city deserves a winner, and so do all those guys who’ve been here over the years.”2

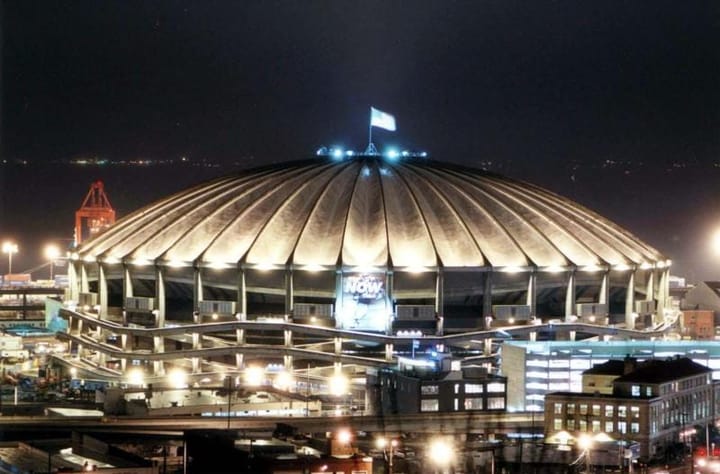

The Mariners returned home for a 3-game weekend series to close out the season. The game on Friday was Fan Appreciation Night and a near sellout crowd was expected at the Kingdome, the perfect setting to become winners.

But because these are the Mariners we’re talking about, they couldn’t just have a fun little weekend and celebrate their best team in history without a little drama on the side.

On the morning of October 4th, the Mariners made front page news when a source leaked to the Seattle Times that they were firing manager Jim Lefebvre.3 The winningest manager in Mariners history and they decided to get rid of him before the season even ended. General Manager Woody Woodward had been looking to make a change at manager since the previous winter. His main target was former Yankee player and manager Bucky Dent.4 Reds manager Lou Piniella and Mariner third base coach Bill Plummer were also said to be in the running.

Owner Jeff Smulyan was in favor in Lefebvre as manager, which seemed to give him security despite Woodward’s wishes. However, Lefebvre bemoaned Smulyan’s incompetence at running the team that summer, blaming his financial problems on the team’s inability to obtain a right-handed bat to help them improve. Although it is accurate to say that if you’re having trouble finding a righty hitter you have some issues, those comments likely sealed Lefebvre’s fate.

The Mariners ownership and front office denied that a final decision had been made, but they all offered up concern that Lefebvre had lost respect in the clubhouse. Whether that was true or not, the team was on the brink of a winning season and had three chances to win one more game. Everyone wanted that win.

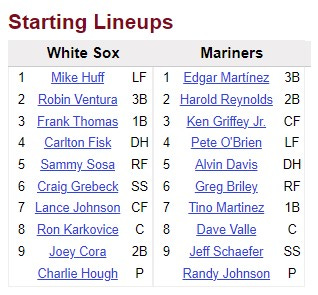

Getting one more win wasn’t guaranteed, though. The Mariners’ opponent for the final series of the year was the Chicago White Sox. The 1991 White Sox ended the year with a record of 87-75, good for second place in the American League West.

The Mariners indeed had a near sellout crowd on Friday, October 4th as 55,300 fans filed into the Kingdome hoping for a win.

With two outs in the bottom of the first inning, Ken Griffey Jr. got the Mariners going with a line drive single. Then, he stole second base. Griffey had had an impressive season. He’d end with exactly 100 RBI, which made him the youngest player in the majors with 100 RBI since Al Kaline in 1956. Griffey joined only 17 other players to drive in 100 runs in a single season before the age of 22. His was also only the 4th season in which a Mariner player had accomplished the feat (Alvin Davis twice, Jim Presley, and Willie Horton). Taking advantage of Griffey in scoring position, left fielder Pete O’Brien drove a ball to right center field to score the first run of the game.

In the top of the second inning, the Mariners were given a gift when Craig Grebeck appeared to score on Joey Cora’s sacrifice fly. Home plate umpire Tim McClelland called him out. In the bottom half of the inning, right fielder Greg Briley hit a leadoff triple and later scored on a Dave Valle sacrifice fly.

O’Brien got in on the sacrifice fly action in the bottom of the third inning. Harold Reynolds led off with a single and a steal of second. He advanced to third on a Griffey single and scored on O’Brien’s fly ball.

The Mariners took the 3-0 lead into the top of the fifth inning when Randy Johnson ran into a little bit of trouble. Johnson finished the 1991 season giving up more walks (152) than hits (151). In this game, he walked 7 and only allowed 3 hits. Unfortunately, those hits took a toll in the fifth when Robin Ventura singled home Ron Karkovice, who had reached on a leadoff double. Carlton Fisk scored Mike Huff, who reached on a walk, with a sacrifice fly. During the inning, Johnson twisted his right knee, but powered through and despite the hiccups, the Mariners held on to a 3-2 lead.

Calvin Jones replaced Johnson in the 6th inning and the White Sox struck again when Grebeck scored on a Cora bunt groundout. Jones earned a blown save, but the Mariners were determined to get that lead back and get a win.

In the bottom of the sixth, the Mariners took the lead back for good. Valle singled home Briley and Jeff Shaefer, filling in at shortstop for Omar Vizquel (out with the flu) singled home Jay Buhner, who had entered the game as a pinch runner for Tino Martinez. Michael Jackson and Russ Swan held the lead for the Mariners and Mike Schooler closed it out and the Mariners were a winning team for the first time.

Alvin Davis was jubilant after the game, telling the Seattle Times:

"Winners . . . we're winners," said a joyous Alvin Davis, who has waited and wondered longer than any other Mariner. "It means so much to those of us who've been here. The young guys look at our happiness and ask, `What's the big deal?'

"But this means more than winning a pennant. That kind of joy is in the heart. This emotion comes deeper in the body, in the gut.

You have to come back the next year and win a pennant over again.

But this was something they can never take away from us, a forever thing."5

They beat the White Sox again the next night for their 83rd and final win of the season. Turns out, it was possible to have winning baseball in Seattle after all. The Mariners broke the 2 million attendance mark for the first time that year too. If you win, they will come.

Still, during the final series of the season everyone wondered if this one winning season was all they’d ever have. Smulyan was threatening to move the Mariners to St. Petersburg, Florida. There were doubts the Seattle Mariners would even exist in 1992.

Lefebvre was indeed fired after the season. He was replaced by Bill Plummer and the 1992 Mariners only managed a 64-98 season. But 1992 was the year Smulyan sold the team to Nintendo and in 1993, even though the threat of relocation continued to hang from the Kingdome rafters, everything began to turn around.

It was because of the 1991 team that the Mariners finally reached an important milestone. 1991 gave us a measure of hope that maybe, just maybe, the 90s would be a better decade for baseball in Seattle.

Beer and Batting Averages

The Mariners’ starting catcher was Dave Valle in 1991, and 1991 was a rough season for Dave. I’ll simply point out that he slashed .194/.286/.299 and we’ll leave it at that. While he was struggling, a bar in Pioneer Square came up with a promotion that lives forever in Mariners lore.

Swannie’s Sports Bar was familiar to fans who frequented the neighborhood. It was owned and operated by Jim Swanson, who you will remember as the left-handed catcher for the Portland Mavericks. He learned the bar trade from his Mavericks manager Frank Peters and when the Mavericks’ run was over, he came north and opened his own bar. (Swanson died a couple years ago; Larry Stone wrote a nice piece about him.)

Swannie wasn’t much of a hitter himself. According to Baseball-Reference, he slashed .167/.286/.258 over a 40 game career. Those numbers may not be totally accurate, but he did say for his career he was under the Mendoza Line. So, he probably felt some affection for his catching counterpart on the Mariners. He started a promotion where beer and well drinks at his bar cost the same as Valle’s batting average. For the season, the average price was $1.94, and often lower (the equivalent of $4.54 today, a real bargain!).

Valle himself wasn’t a fan of this promotion. He was about as opposite of the players on the Mavericks as you could imagine. He was quiet and religious, and didn’t enjoy being associated with a beer price promotion. He also didn’t enjoy fans yelling at him from the stands and asking for the price of beer that day. Valle didn’t complain to reporters, but his feelings on it were clear.

From the Seattle Post-Intelligencer:

“I know Dave is upset and I can understand where he's coming from because of the image he's trying to project,'' Mariners teammate Alvin Davis said last night. “If he was the type of person who frequented an establishment like Swannie's it would be one thing, but he doesn't want his name associated with something like that.”6

Swanson took Valle’s feelings to heart, and removed signage advertising the prices, although the promotion continued through the end of the season.

While We’re Here, Another Dave Valle Story

Around this time, Dave Valle coached my brother’s indoor soccer team. I remember everyone thinking it was pretty cool a Mariner was coaching the team (his son was also playing on the team). After the season, Valle had a party at his house for the team and invited Ken Griffey Jr. to make an appearance. As you can imagine, all those kids were super excited to see THE Ken Griffey Jr. They swarmed him and were touching his fancy car and getting sticky fingerprints all over it. Understandably, his appearance there was short, but at least it was memorable.

https://www.britannica.com/topic/Seattle-Mariners ↩

SHERWIN, BOB. ".5JUBILANT MARINERS FIND 81 REASONS TO CELEBRATE AFTER WIN OVER TEXAS ASSURES THEM OF PLACE IN HISTORY." THE SEATTLE TIMES, October 3, 1991: E1. ↩

FINNIGAN, BOB. "FOR LEFEBVRE, IT'S GOODBYEMARINERS WILL FIRE WINNINGEST MANAGER BY MIDDLE OF NEXT WEEK, SOURCE SAYS." THE SEATTLE TIMES, October 4, 1991: A1. ↩

Every time I see Bucky Dent mentioned I can hear my Red Sox fan father screaming his name with an expletive wedged nicely in the middle. He may have refused to take me to any games had Dent ever been hired as manager and my whole life could be different. ↩

FINNIGAN, BOB. "M'S TAKE GOOD WITH THE BAD55,300 ARE WITNESS TO SEATTLE BASEBALL HISTORY." THE SEATTLE TIMES, October 5, 1991: B1. ↩

Street, Jim. "CHEERS? GIMMICK NO HIT WITH VALLE - BARS LINK DRINKS TO HIS BATTING AVERAGE." Seattle Post-Intelligencer, August 22, 1991: D1 ↩

Comments ()