The Expansion of the Cactus League, the Pilots, the Mariners, and the First Man To Lose His Mind Over Seattle Baseball

What’s more American than apple pie and baseball? A lot of unsavory things, but for our purposes today, lawsuits!

Hello everyone! I can't believe it's been so long since I've gotten a newsletter out. I've been distracted by moving it and with, well, everything else. I've still got a few wrinkles to iron out, but we should be getting back to normal here. One note on this post: I'm still figuring out how to do footnotes. It's quite a bit more complicated than it was at Substack (and honestly one of the reason I hesitated to move). You may not care much about them, but I'm a fan of citing sources and all that. I'm working on finding a nice way to do it, and then I'll probably update the post online. In the meantime, here's today's story!

Seattle was officially awarded its second major league franchise on February 7, 1976. The franchise that would be named the Mariners was born of a lawsuit against the American League for allowing Seattle’s first major league franchise, the Pilots, to leave town after a bankruptcy that was embarrassing for everyone involved. Whereas the American League shouldn’t have awarded the Pilots to Seattle based on the tentative financial state of its ownership group, the Mariners began their existence with relative financial stability, a brand new domed stadium, and the expectation that this team would stay in town.

In the spring of 1977, the Mariners embarked upon a fresh start for major league baseball in Seattle. They made their way to their first spring training with no idea that they were walking right into a mess that began with the Seattle Pilots in 1968.

*****

The Cactus League was officially established in 1947. By the time our story begins, it had five members: the Athletics, Cubs, Giants, Indians, and Angels (who were listed as part of the league even though they trained in Palm Springs).

As the business of spring training blossomed, more cities in Arizona wanted to take advantage of the opportunity to draw baseball tourists and money. In Tempe, a baseball fan with an eye for a business opportunity saw a way to make some money of his own at the business of spring baseball.

He was E. B. Smith and he had a visions of an all-purpose baseball facility in Tempe. It would have a stadium for games, full-size practice fields, hotels for players and fans, dormitories for minor leaguers and staff, apartments with a view, and restaurants and shops to provide entertainment beyond baseball. He zeroed in on an area in Tempe called Double Butte. In exchange for finding a tenant and handling the logistics of building the complex, his company, Baseball Facilities, Inc., signed a 99-year lease with the city of Tempe in 1966 for the city-owned land at $1 a year. Sounds like a real bargain.

Smith’s first target to occupy the envisioned facility was the Los Angeles Dodgers. They opted to stay in Vero Beach, Florida and Smith turned his attention to the Cincinnati Reds. He was close to a deal to lure them from Tampa to Tempe, but the Reds also opted to stay in Florida.

The American League helped him out when it made plans to expand in 1969. The league needed to quickly replace the Athletics in Kansas City after the team moved to Oakland, and wanted to expand to the successful minor league city of Seattle before the National League got there. Ready or not, a team was granted to Seattle and the Pilots began their financially precarious journey.

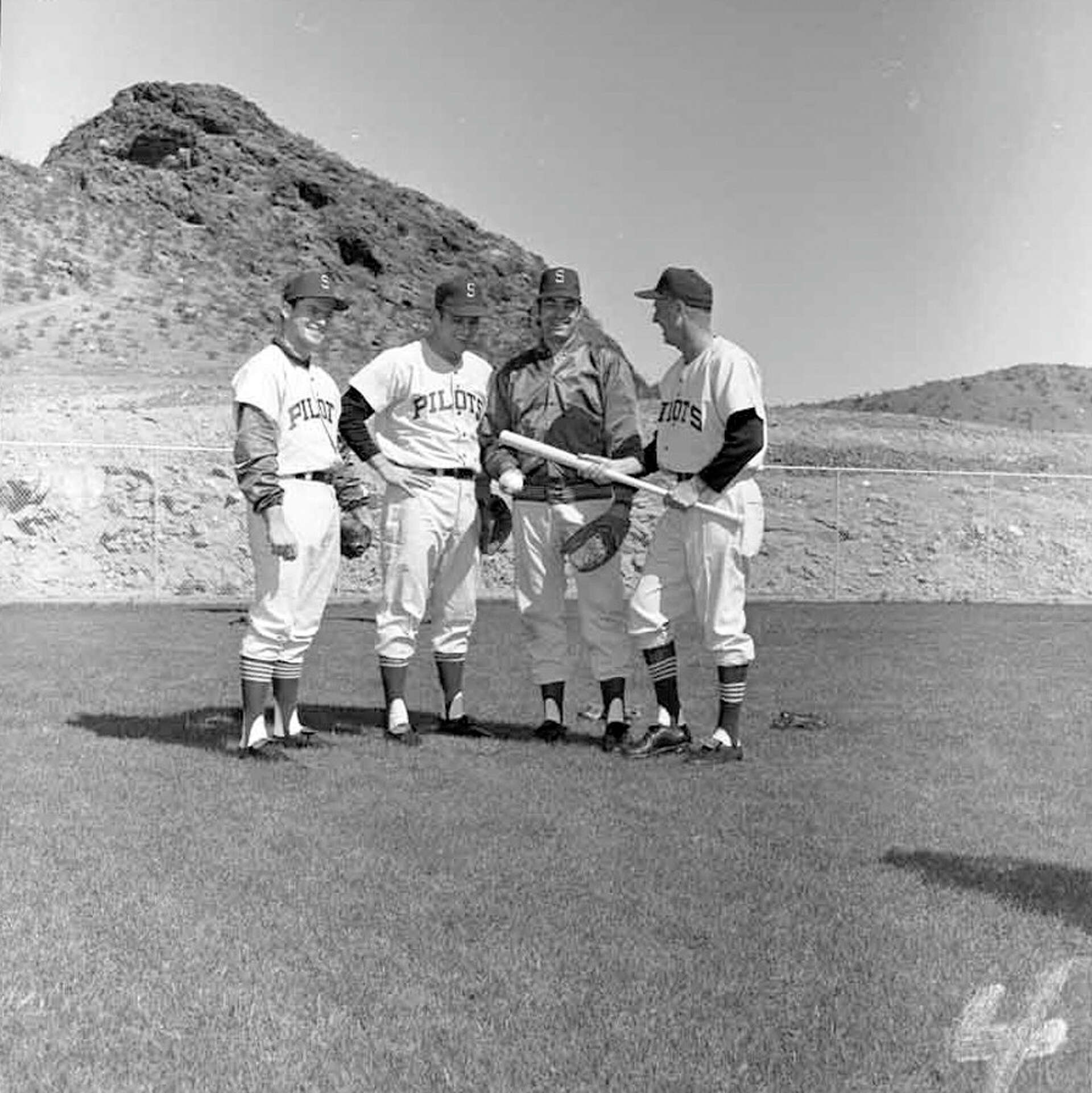

What did a brand new baseball team need, but a brand new spring training facility? He flew to Seattle for the 1968 opening of the last Pacific Coast League opening day there. He met with the Pilots' owners, brothers Dewey and Max Soriano. The Sorianos had been involved in local baseball and the Pacific Coast League for many years. The view of the American League and Smith was that they knew how to make a baseball team successful.

On April 29, 1968, the Pilots announced they had chosen Tempe as their spring home. Under the agreement, the Pilots, operated by Pacific Northwest Sports, and Smith’s company, Baseball Facilities, Inc., formed a subsidiary called Pilot Properties to undertake the development venture. PNS held 60% of Pilot Properties, granting BFI 40% of the stock.

Smith wanted a long-term lease for the new facility and the Pilots obliged, signing up for 20 years, with two five-year options tacked onto the end. BFI contributed some capital to build the stadium and practice fields and the Pilots agreed to provide the rest to construction improvements, including the motel, dormitory, streets, and utilities.

Construction began in July 1968 as newspapers gushed about the new, state of the art facility. Major league baseball was coming, not just to Seattle, but to Tempe as well.

*****

The first hint that things were going to go off the rails for the Pilots arrived not too long after ground was broken at the facility. Given the multitude of things that needed to be done to get ready for an expansion team, including costly renovations of their regular season home ballpark, Sicks Stadium, the Sorianos weren’t nearly as focused on the development of their spring stadium. Nor were they eager to spend money they didn’t have to spend.

But Smith had invested years of his life into the Tempe project. This was his baby and it had to go exactly the way he wanted it to. When the Sorianos didn’t follow through on contributing the money for the improvements they’d agreed upon, and when Smith didn’t feel like he was getting their full attention, he went to the courts.

On December 12, 1968, he filed suit in Phoenix District Court alleging that the Sorianos and Pacific Northwest Sports had violated parts of the Securities Exchange Act and the rules of the Securities Exchange Commission due to the exchange of stock in Pilot Properties as part of the agreement between BFI and PNS. Smith asked for a total of $6 million in damages and that the lease agreement with the PNS be rescinded, leaving the Pilots without a spring home.

A lawyer for the Sorianos characterized the suit as a nuisance, and hearings for the suit were postponed at the request of both sides as the calendar turned to 1969. Now they were worried that Smith was mad enough to interrupt spring training and disrupt the Pilots’ preparations for their inaugural season. Smith said they had nothing to worry about. “I like baseball too much. I wouldn’t do anything like that,” he told Hy Zimmerman of the Seattle Times.

The Pilots began spring training without incident from Smith. While the Pilots were training, lawyers on both sides filed briefs in court. One of the major issues the Sorianos wanted addressed was Smith’s role with BFI. They felt he was unnecessarily antagonistic toward them and wanted him out of the picture. Smith felt he had invested so much time and effort in the facility and refused to give up his role, even for the good of the project.

In April, the Pilots headed north for the franchise’s only season in Seattle. In Arizona, the legal battle continued until the end of May. Then the Phoenix District Court dismissed the $6 million suit brought by Smith against the Sorianos. It appeared that the legal battle was over.

*****

As Pilots' the financial troubles grew impossible to hide over the course of their only season, the Sorianos tried to find local ownership, money, and capital, but failed on every count. As they lurched toward a sale at best and a bankruptcy at worst, and Smith added to their troubles by threatening to lock the team out of spring training. The Pilots, he said, were a half-million dollars in arrears for the funding of Pilot Properties. BFI, Smith said, “is prepared to take steps to keep the Pilots out unless they fulfill their contract.” He went so far as to claim that the Sorianos had taken the profit from spring training for personal use, instead of investing it back into Pilot Properties. Smith also claimed they were missing out on $130,000 in revenue for the facility because the Sorianos had not funded the motel, convention center, apartments, and health club that was part of the agreement.

Smith was furious at the situation and did not let an opportunity pass to lash out. “You really have to work at losing a major league franchise in one year,” he sneered to reporters, “but they are capable of it.”

Without the $500,000 the contract called for, Smith threatened to lock the Pilots out of the facility. The Pilots managed to appease Smith enough to train in Tempe in 1970, obtaining a guaranteed note of $500,000 from First National Bank of Phoenix. The security for the note was the land lease of 99 years. The worry was floated that if Pacific Northwest Sports lost the ability to operate the Pilots, the lease would be invalidated.

As the American League owners were meeting in mid March to announce they would not put any more money into the Pilots, Smith announced that he was canceling the contract with the team because the Pilots had failed to comply with the agreement for the use of the facilities. He magnanimously allowed them to use it on a day-to-day basis for the rest of the spring.

As bankruptcy began to look like the only option for the Pilots, Smith panicked about being left with the debts from the Pilots. He took over the facility, personally collecting the money from concessions. Even though it wouldn’t come close to financing the debts, he was grabbing everything he could. In his desperation, he filed another lawsuit against PNS and the Sorianos, asking for $1 million in damages for the investors in BFI.

In response, Pacific Northwest Sports filed a counter claim contending that “Smith interfered with, harassed and attempted to discredit Pacific Northwest, and should be enjoined from any further action on behalf of Pilot Properties.” Smith responded by filing a $4 million suit that also asked for full control of Pilot Properties.

When the bankruptcy hearing began in Seattle, Smith headed north, believing his squabble would prove important. He came forward near the end as a voluntary witness. The bankruptcy judge did not consider the Tempe facility “germane to his ruling and declined to hear Smith.” This, naturally, did not quell the rage Smith felt toward the Sorianos. As everyone left the courthouse, he was overheard yelling down the hall, “Wherever they go, whatever they do, they are going to know that somewhere out there, I’m watching and waiting.”

As we know, the Pilots were awarded bankruptcy and the team moved to Milwaukee and became the Brewers. If only that had been the end of the legal troubles.

*****

In the summer of 1970, the city attorney of Tempe recommended that the city repossess the land. BFI and Smith argued the city should wait until the court case between BFI and PNS was resolved. In addition, Tempe began questioning whether the 99-year lease it has signed with Smith and BFI was legal. It was also revealed that the city attorney who had worked on the lease with Smith left the city and took a job with an attorney for BFI.

Although the Brewers inherited a lease for the stadium, they were displeased that the dormitory and cafeteria had not been built as promised. In early February 1971, the Brewers jumped into the lawsuit game, filing suit in Maricopa County Superior Court asking that their contract be voided. The Brewers told reporters they simply wanted to “clear up the legality of the lease.”

With the suit pending, the Brewers trained as planned in Tempe, but Smith transferred his rage at the Pilots onto them. The Brewers had a deal to make a monthly payment for the use of the facility. Smith claimed they had not made their payment so on March 8, he showed up at the facility early and immediately fired the entire grounds crew and all the stadium workers. He then turned off the gas, electricity, and the water and told the Brewers to “take your team to Alaska!”

A Brewers spokesman told reporters the team had in fact made its monthly payment, and instead of going through Smith had made the payment directly to the bank. After Smith’s actions, the holder of the mortgage, First National Bank of Arizona assumed control of the facility. The utilities were reconnected and the workers all rehired. The game that evening went off as planned.

A result of the spring brew-haha (it’s illegal to write about any sort of excitement with the Brewers and not make this joke) was that Smith was removed from the board of Pilot Properties. He also claimed the stress of the situation, first with the Sorianos, then with the City of Tempe and Brewers had caused him to have two heart attacks.

The Brewers trained in Tempe in 1972 once again. During spring training a judge ruled that the lease between Tempe and Baseball Facilities, Inc. was valid and constitutional. After that ruling, Smith offered to transfer the stadium facilities to the city in exchange for a $165,000. He also filed suit once again, this time against the Brewers and Tempe, claiming they conspired to invalidate the lease.

Over the summer the stadium fell into disrepair. The city, bank, and Smith argued over who was responsible for maintenance. In November, Smith filed another suit against Tempe, claiming that the unsuccessful lawsuit against BFI over the lease had caused BFI to be unable to successfully promote the stadium.

The Brewers were clearly tired of the battles. In early 1973, they terminated their lease, paying $400,000 to First National Bank to pay off the loan the Pilots had obtained. Now BFI had control of the facility. With the Brewers out of the picture, the only opponent remaining was the City of Tempe.

*****

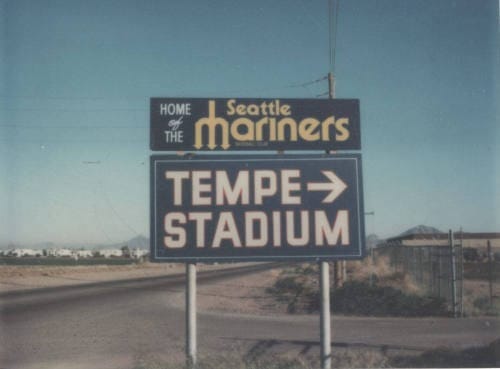

The Brewers moved to Sun City for spring training in 1973, and Tempe would not reel in another team until the Mariners began training there in 1977. In the interim, the lawsuits did not stop. Smith and BFI sued the City of Tempe, the City of Tempe sued them back, rulings were appealed, and no peace was found over the years. They fought over issuing permits for events, and the question of the lease never faded. We don’t need to get into the weeds here; suffice to say, it remained a quagmire.

E. B. Smith was still determined to bring a major league team to his facility in Tempe. When it was announced that Seattle would get a team once it dropped its lawsuit against the American League, Smith was on the phone to Lester Smith and Danny Kaye, the new owners, before the franchise had officially been granted.

Even while a lawsuit was pending between BFI and Tempe, with Smith claiming the city was trying to force his company into bankruptcy, new Mariners general manager Lou Gorman toured the Tempe site in April 1976.

In July, the Mariners signed an agreement to train in Tempe. They joined the Giants, Cubs, A’s, Brewers, Padres, Cleveland, and Angels in the Cactus League. It was a bold move choosing the same site that had kicked off the Pilots’ existence. Surely, they must have thought, it’ll be different for us.

*****

The first sign that it wouldn’t be different for the Mariners, that they were wading into a mess the Pilots made, began with a literal mess.

In February 1977, before the official reporting date, a number of players were already in Tempe and eager to kick off a new baseball team and season. Among them was outfielder Steve Braun. Since workouts hadn’t officially begun, he brought his German Shepherd puppy with him to work one day. The puppy did what puppies do; it left a mess on the floor. Unfortunately, this mess was left at the office doorstep of none other than E. B. Smith. Of the incident, Hy Zimmerman wrote in the Seattle Times that “An enraged Smith immediately framed a no-dogs edict.”

The next target of Smith’s rage was Hal Childs, the Mariners public relations director. As the Mariners public relations director, Childs went to city hall in Tempe and invited Mayor William LoPiano to the Mariners Cactus League opener, leaving tickets for the mayor as well as other city employees. It is, after all, a good move to establish a good relationship with the local government.

LoPiano served as mayor of Tempe from 1974 until 1978. He was invested in expanding Tempe’s downtown business district and made the smart sartorial choice of plaid suits in many of his official portraits and appearances. LoPiano was also not a fan of Smith. As the proprietor of facility, Smith had originally sent tickets to the mayor. LoPiano wrote “void” across the tickets and returned them unceremoniously.

When Smith, described by J Micheal Kenyon of the Seattle Post-Intelligencer as “flamboyant and emotional”, heard that Childs had given the mayor tickets, he flew into his second rage of the week. While the Mariners were out on a practice field for several hours of drills in the Arizona sun, Smith screamed down the hall, “You, Hal Childs! If you are not off my property in ten minutes, I’ll turn off the water! And if that doesn’t do it, I’ll start changing the locks!”

Smith later raged to the media about the situation, “The Pilots tried to sneak around behind my back, the Brewers tried it and now this…No bleepin’ baseball team is going to bleepin’ run over the top of me!”

He explained his feelings toward LoPiano saying, “He and the city have fought me, not cooperated with me and have cost me practically a half million dollars in legal fees trying to break my lease…If (LoPiano) shows up for the opening exhibition, I’m not letting him in!”

Despite the threats, the Mariners fared better than the Brewers had and kept not just the hot water, but all running water.

The next day, Smith showed up to the facility, if not chagrined, at least calm. “I don’t want to hurt the Mariners,” he said. “They are just too nice an organization. I mean that. They have a class operation.”

Smith also backed off on threatening to keep LoPiano out of the ballpark. In fact, he sent a letter asking him to join in the opening day ceremonies.

Before the games could begin, there was another issue that needed to be addressed: the sorry state of the playing fields. In early 1977 the Arizona Republic gushed about the refurbishment of the stadium, including the new sod in the main stadium and sprucing up the practice fields. When the Mariners arrived, they found the fields were less than stellar.

Mariners players dubbed the two practice fields Iwo Jima and the Alligator Pit. The Seattle Post-Intelligencer wrote that they were so nicknamed because of the “rather rough-hewn infields and the fact that tall clumps of dry grass and weeds are not altogether uncommon in the outfield, particularly in the Alligator Pit.” You know things are going great when a field of play is named after a major battle in a major world war.

The main stadium had problems of its own. In the infield, the distance between the bases was 88 feet, the infield was riddled with rocks and stones, the pitchers mounds was wonky, and the outfield grass wasn’t growing the way it should have been. This was a facility that Lou Gorman claimed was “considered the finest complex of its kind in the area” before signing the training agreement with Smith.

Manager Darrell Johnson knew they could not play on those fields, and the main stadium field in particular would be embarrassing when they began hosting games. He gathered the intrepid grounds crew and joined them, attempting to bring the field closer to a major league level.

Over the course of a day, Johnson himself “spent four hours distributing dirt, raking it, rolling it and watering it under a patient but broiling Arizona sun.” He also reshaped the pitchers mound. J Michael Kenyon on the Seattle P-I asked how it was going. “At this point in spring training,” Johnson quipped, “the grass is ahead of the dirt.”

*****

Despite the drama, the Mariners successfully completed spring training and left for Seattle to begin their first season. The legal fighting in Arizona, on the other hand, it just continued.

This time, the lease the City of Tempe signed with BFI was declared unconstitutional and a subsequent court decision held that Tempe should pay for the value of improvements to the land. The City Council authorized paying $471,000 in restitution, but there was still a question of who actually controlled the stadium. Furthermore, Smith was planning to appeal the award because he felt it was too low, having asked for $760,000. The Mariners were caught in the middle of the legal fighting that was stretching close to a decade.

It looked like the facility would not be available for the Mariners instructional league team, and worse still, it was possible they would not be able to use it for spring training in 1978. Smith flew to Seattle in July 1977, trying to convince the Mariners to sign a 25-year lease. The Mariners wisely turned him down. Smith threatened to completely close the facility down, saying without the lease he could not pay maintenance costs. One year still remained on their current agreement, however, the legal actions meant the site was in abeyance and the use depended on whether or not Smith appealed.

Finally, FINALLY, it all came to an end. In November 1977, the City of Tempe reached an agreement to take control of the complex away from Smith. The city Parks and Recreation Department took over managing the fields and facilities, and without the blustery Smith, the Mariners made Tempe their spring home until 1991.

If there’s any lesson we can learn from the legal drama in bringing major league spring training baseball to Tempe, it’s that the real national pastime was all the lawsuits we filed along the way.

Comments ()