Lies! Damned Lies! And the Things They Told Us About Safeco Field

You know the urban legend about how a library was built and they forgot to factor in the weight of the books? It's like that, except they forgot to factor in that they would be outside in Seattle.

In the 1990s, baseball fans were nostalgic. Baseball fans are always nostalgic; it’s kind of what we do. In this case, we were nostalgic for the ballparks of yore. The brick, the coziness, the old time architectural touches.

So, baseball began tearing down real vintage stadiums and replacing them with fake vintage stadiums.

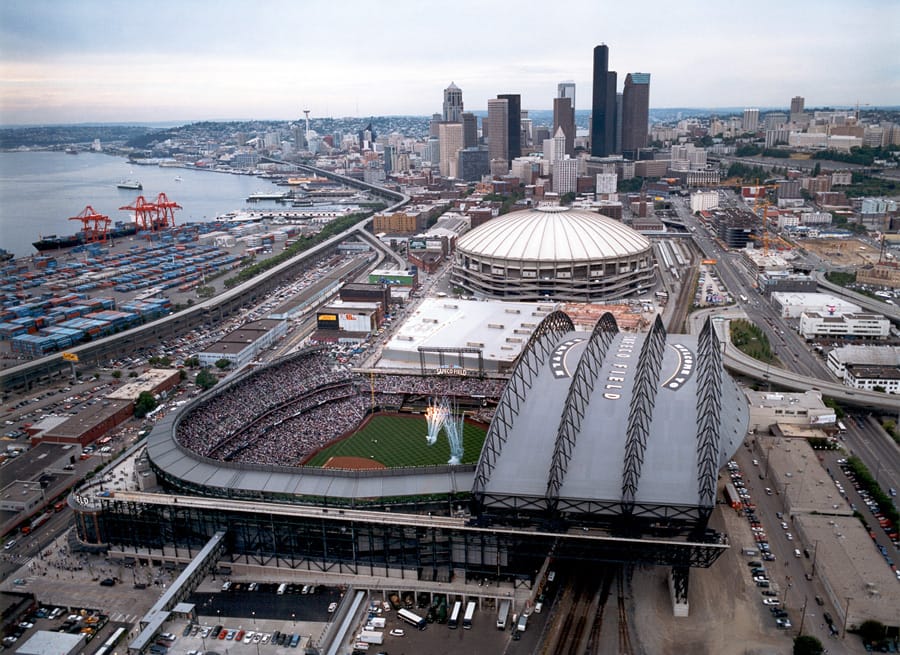

After every Mariners owner complained about the Kingdome, whined that it was impossible to make money with such a bad stadium (never mind the bad baseball team), and threatened to initiate a second relocation of a Seattle Major League Baseball team, politicians got together and decided to build a fresh new ballpark over the objections of voters. It would be built in the vein of the classic ballparks of yore. It would become a civic treasure where generations of baseball fans would fall in love with their team.

The politicians and the civic planners did their thing and negotiated contracts, approved plans, made threats to obtain more public money, and fought off lawsuits, and construction got underway (interrupted periodically by more lawsuits and more threats for more public money).

Naturally, there was a lot of hype leading up to the opening of the new ballpark. This was some seriously exciting stuff. A real ballpark, a charming ballpark, on the edge of downtown Seattle.

Maybe it was wishful thinking, maybe it was getting caught up in the excitement of the idea that this new ballpark would completely change the team and its relationship with the city and fans, but the reality of the stadium turned out to be a bit different than the gushing of stadium planners and our own fanciful daydreams led us to believe.

Mid-summer 1999 we knew the new ballpark would be different than the Kingdome, but none of us were prepared for how far it would skew as a pitcher’s park. And though there were certainly voices of caution, some of the ballpark design had us dreaming dreams that would never come true.

This is a look back at the things we thought and were told before Safeco Field opened.

It Won’t Be a Hitter’s Park, It Won’t Be a Pitcher’s Park, It’ll Be a Fair Park

Most of our time today will be spent on the ways the park has not been good for offense. It is, after all, one of the most well-known features of our dear field.

The Kingdome was notoriously home run friendly and rough on pitchers, so the architects of the new ballpark wanted to make the field play a little more fairly. They also wanted to avoid the Camden Yards problem: a ballpark so notoriously tiny and home run friendly, it was seen as the coming of a baseball apocalypse.

“Creating a launching pad was a concern, and still is,” Mariners assistant general manager Lee Pelekoudas said when a model of the new stadium was unveiled. “The fences are too close in Camden…It’s ridiculous.”1

The exact distances hadn’t been nailed down yet, but everyone knew this ballpark would have a big outfield to avoid the Camden Yards problem and to give pitchers breathing room after the Kingdome. The distance down the lines was about the same as the ‘Dome, 331 and 327 feet to left and right respectively. But the center field fence was originally conceived at a whopping 422 feet2 away from home plate (to put that in perspective, the furthest distance in an MLB ballpark is 415 to center at Coors Field…just imagine for a minute a 422 distance in Seattle).3

The power alleys were deep too. Originally, left-center was designed to sit at 410 and right-center was 386. Still, the distance down the right field line was optimistically deemed advantageous for Ken Griffey Jr’s career home run totals. It “should accommodate a couple of hundred home runs before his career is over,” wrote the Seattle Post-Intelligencer.4 (He hit 29 home runs at Safeco Field in his career.)

Luckily, the architects took feedback from key Mariners players and after discussions with Ken Griffey Jr., Jay Buhner, and Edgar Martinez made a few adjustments. Center field came in to 409 and left center to 400. The players also suggested bringing the outfield wall down to 8 feet high. All the easier for Griffey to jump up and rob opposing home runs.

“Our goal is to ensure that Safeco Field is built as a fair ballpark; not a hitter’s paradise, not a pitcher’s park, but a fair park,” Mariners General Manager Woody Woodward said of the changes.5 The ballpark was still big, and because Major League Baseball had just added two new teams the Seattle Times boosted that making a larger park was a good idea because “pitching will be further diluted by expansion.”6

Because of this ballpark we have all learned about the marine layer, which seems to exist solely to thwart any hope of developing a serviceable offense. And it could be a case of hindsight, but it’s fair to ask, “Did anybody involved in this project consider the effects of air?!”

Well, yes. But, they didn’t expect it to affect offense as much as it did. Remember, a lot of the focus was on not building a home run launching pad. They didn’t even consider they’d have to make it the size of a Little League field before they had to worry about that.

In early 1998, Lou Piniella took a tour of the ballpark-in-progress. He played three seasons in the Pacific Coast League and came through Seattle during the Pilot’s sole season in 1969. He recalled that “the ball carries well here outdoors. It’s a lighter air. Although when it’s cold in the spring, the first six weeks or so of the season, the ball might not carry as well. But as the weather warms up, it will go.”7

Edgar Martinez had played in Tacoma and Vancouver B.C. and remembered it differently. He was concerned that hitting wouldn’t be easy. “You’re not going to have the dense air (in the Kingdome) like it could be in the new stadium…some balls we hit here in the gap that go out, there’s a good chance they won’t go out.” Jay Buhner added, “This is an outdoor ballpark, it’s a little cooler and I think history has shown that in these types of ballparks, the ball doesn’t carry quite as well.”8

Mariners hitters had been concerned about how the ball would carry since they took an impromptu batting practice on the field while the stadium was under construction in mid-1998. Tim Wendel at The National Pastime Museum wrote of their excursion:

The builders and Mariners front office assured people that even if there was an effect on offense, it was impossible to know what exactly it would be before the games were played. The fences, they said, can always be adjusted.

As you probably know, the fences were moved in before the 2013 season. Yet, the Mariners still can’t hit there. In fact, it is still the worst park for offense in MLB.10

But thank goodness they avoided the Camden Yards problem!

You Can Stand Outside on Royal Brougham Way and Collect Home Run Balls

After the Mariners had closed out the Kingdome and before they would open Safeco Field, the 1999 All-Star Game was played at Fenway. During the Home Run Derby, television audiences watched fans standing outside on Lansdowne Street, behind the Green Monster in left field, scooping up home run balls. This also happened during batting practice, and occasionally during a game. It seemed conceivable that this could be the scene in a few days on Royal Brougham Way, the street that ran along the left field side of the Mariners’ new ballpark.

On this side of the ballpark, fans walking outside could catch glimpses of the field through the gates. They could see and hear and smell the game, and maybe, catch a long home run. It was a stretch of the ballpark that was supposed to bring the community into the game, even if only figuratively, and a way to let the game and the team seep out into the city.

After Mark McGwire hit that monster home run that practically bounced off the back wall of the Kingdome, the Mariners were quick to point out that the home run “would have gone out of the new stadium, landing on Royal Brougham and rolling into the Kingdome’s south parking lot.”11

But again, baseball was being played outdoors. And the size of the ballpark didn’t accurately factor in the effects of sea-level air and the marine layer that would torment batters in Seattle for the next 25 years and counting.

In fact, a ball wouldn’t leave the confines of Safeco Field until August 14, 2004 when Gary Sheffield hit a foul ball that landed near the glove sculpture by the left field gate.12 I can’t seem to find an accurate count of how many times it has happened, but I can only remember one other ball leaving the ballpark (and I don’t remember who hit it and my newspaper and internet searched aren’t coming up with anything, but I believe it was during batting practice).

I’ll admit a part of me worries about the safety issues of a hard baseball randomly plummeting down toward the street outside the stadium, but I can’t resist the images of fans gathering out there, and extending the reach of baseball magic beyond the confines of the park. Those little touches can go a long way in building goodwill between a team and a city, and create opportunities for treasured baseball moments.

Home Runs Will Bounce Off the Hit It Here Cafe ALL the Time

The Hit It Here Cafe was named for a Ken Griffey Jr. Nike commercial and designed to give fans a sit-down dining experience in a casual sports bar atmosphere. The ticketing and rules of the Cafe changed quite a bit over time, but the idea was you could enjoy a sit down meal while periodically being startled by a ball hitting the glass walls. This has certainly happened! And, if you got a spot in there during batting practice, you were sure to enjoy a few plunks.

But not too long into its existence, the Hit It Here Cafe faded from being a fun ballpark feature to something that was just there. A handful of home runs a year does not a home run attraction make.

The signage and bullseye are no longer on the facade of the cafe. The marine layer claimed another victim.

The Train Whistles Will Be Charming

Airplanes were part of the ambiance of Shea Stadium in New York, and trains would be part of baseball in Seattle. The whistles would be lovely background noise we’d hear a few times a game, a gentle auditory anchoring of place.

Nope.

I understand that my opinion on this is controversial. Some people loved the train whistles. I did not. Train whistles are loud. Loud and annoying. And thankfully silenced now. Once the stairs and pedestrian bridge were built and the tracks closed off, it no longer became necessary for trains to sound their horns at that intersection.

My ears have almost stopped ringing from the constant auditory attacks.

It Will Be the House That Griffey Built

Maybe it still is. I suppose it depends on how you want to look at it. If any single moment can be credited with creating Safeco Field, it was Ken Griffey Jr. sliding into home to win Game 5 of the 1995 Division Series.

We had visions of Griffey roaming center field on the grass surface we hoped would keep him healthy. We anticipated seeing him top Henry Aaron’s home run total outside on a pleasant Seattle summer night. He was then the player in baseball that everyone thought had the best chance at that record.

The reasons Ken Griffey Jr. wanted to leave Seattle are many. For all his charisma, he didn’t enjoy the fame and instant recognition that came from being Ken Griffey Jr. in Seattle. It was particularly hard to manage while being so far away from his extended family. At times he had a rough relationship with Seattle fans and he, understandably, didn’t enjoy receiving death threats whenever he spoke out. He felt like he gave the team his loyalty and that they often treated him poorly in return. But for all those factors, he still wanted to be Ken Griffey Jr., one of the greatest to ever play the game because he simply wanted to play the game, which meant hitting home runs.

Before construction even began on the new park it was dubbed “The House That Griffey Built”. “I’m not sure if the park does get built without him,” Mariners president Chuck Armstrong said after the groundbreaking in March 1997. General manager Woody Woodward agreed “a very big part, was Ken Griffey Jr.”13

Although he was clearly upset by the batting practice experience in the new stadium, he didn’t complain to the press. But reporters read into it and saw the concern. No one was advocating for a band box ballpark that would artificially boost his home run totals, of course, but we all wanted to watch him hit home runs there. Even when the concerns were brushed off, saying that he was a good enough player to compensate for the size of the yard, they had to make the concession that his numbers would likely drop.

From Ron C. Judd, who was often critical of The Kid, in the Seattle Times:

Even though Griffey, of all players, has the necessary oomph to compensate for Safeco's open spaces, some drop in his output seems inevitable…While we certainly can sympathize with the Mariners' long-pampered batsmen, allow us to respectfully offer three words of advice.

Get over it.

It wasn’t just the dimensions of the new park that upset Griffey. The Mariners also used him in an attempt to exhort more public money from the Public Facilities District board. Mariners CEO John Ellis said that the Mariners’ responsibility for cost overruns could prevent them from signing contract extensions with Griffey and Alex Rodriguez.

Griffey was extremely unhappy to hear about that. “They should (have) thought of that…years ago,” he said angrily. “Every time something happens, it’s always the players…I’ve deferred money. Every time it doesn’t go the club’s way, guess whose name gets dropped in it—mine.”15

He continued that he had give the Mariners and Seattle “everything I’ve got for 11 years. I feel used in this stadium thing, especially when our contracts are not up until next year.”16

I suppose the cost overruns could have cost the Mariners a shot to resign Rodriguez and Griffey. But, the Mariners front office seemed to handle that just fine on their own.

*****

So, here we are, 25 years after the ballpark opened, the worries and obsession with not creating a home run haven are utterly laughable. The stadium has only hosted one playoff game in the last 20 years and the teams have generally stunk.

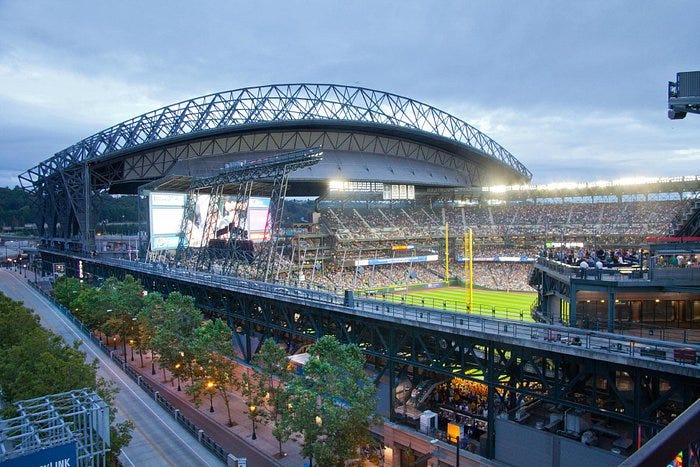

But, as I’m sure you’ve noticed by the pictures here, it’s a beautiful place to watch baseball. And while we’d all like some more offense, I’m not sure there’s any public appetite to sink a lot of money into fixing that. So, the Mariners will Mariner in the ballpark, and we’ll simply enjoy the view and the experience.

But Wait, What About a Curse?

A victim of the marine layer, Teoscar Hernández, won the Home Run Derby this year. He talked to the Seattle Times before his performance and mentioned that he never felt good hitting in that ballpark:

“I talk to a lot of players around the league, and they feel the same thing when they go to Seattle and play two or three games over there,” Hernandez said. “They had the same feeling. So it was not only me.”

Hernandez said he never felt like he was lined up in a straight line with the pitcher’s mound at T-Mobile Park.

What I’m getting from that is simply that the vibes are bad for hitting at this ballpark. We’ve all discussed curses and searched for a reason the vibes are so bad for hitting. I’ve stumbled upon one that I hadn’t seen before.

In March 1999, in a flagrant dismissal of the rules, a construction worker grabbed his bat and stepped into the batter’s box. He “had a friend videotape him as he tossed the ball in the air, hit it and raced around the bases, sliding head-first into home plate without ever losing his hard hat.”18

Because, of course, he couldn’t just be satisfied with that, he brought the video to a local news station, where it aired. He was fired for breaking the strict rules, and said that “One woman…told me I had tainted the field.”19

Only groundskeepers were allowed on the field due to the delicacy of the setup they had for the turf. So, perhaps that little run around the bases disturbed the vibes of the batter’s box. It’s as good a guess as anything else.

FINNIGAN, BOB. "BALLPARK TO BE HITTER FRIENDLY, BUT HOMER-FAIRMODEL FOR NEW SEATTLE STADIUM MAKES HOME RUNS NOT SO CHEAP." THE SEATTLE TIMES, October 25, 1996: C1. ↩

STONE, LARRY. "MARINERS PINIELLA LIKES LOOK OF NEW STADIUM." THE SEATTLE TIMES, February 5, 1998: D1. ↩

The shortest is Fenway’s at 390, but it makes up for it in other ways. ↩

BRUSCAS, ANGELO. "NEW BALLPARK WILL HAVE MORE INTIMATE FEEL." Seattle Post-Intelligencer, October 25, 1996: E1. ↩

STAFF, P-I. "OUTFIELD PULLED IN AT SAFECO - FOUL POLES UNCHANGED, BUT CENTER FIELD SHRINKS." Seattle Post-Intelligencer, December 8, 1998: D3. ↩

STONE, LARRY. "MARINERSPINIELLA LIKES LOOK OF NEW STADIUM." THE SEATTLE TIMES, February 5, 1998: D1. ↩

STONE, LARRY. "MARINERSPINIELLA LIKES LOOK OF NEW STADIUM." THE SEATTLE TIMES, February 5, 1998: D1. ↩

KEPNER, TYLER. "PLEADING BETWEEN THE LINES - HITTERS HOPE IT'S A HITTER'S PARK; PITCHERS HOPE THEY'RE WRONG." Seattle Post-Intelligencer, July 14, 1999: C6. ↩

https://sabr.org/latest/wendel-griffey-and-edgar-and-the-mariners-renaissance/ ↩

https://www.lookoutlanding.com/2023/1/5/23473410/t-mobile-park-pitchers-park-hit-park-factors-effects-marine-layer-safeco-field ↩

STREET, JIM. "JOHNSON UNCORKS MCGWIRE'S BLAST - RECORD HOMER PROVIDES COMIC RELIEF." Seattle Post-Intelligencer, June 26, 1997: D1 ↩

Curiously, even though this was the first time a left the ballpark entirely, it didn’t get much mention in the newspapers. It was acknowledged, but without much detail or fan fare. I just so happened to be working at the left field gate at the time.

There weren’t many of us out there, a few employees and a handful of late-arriving fans. We were all dumbstruck for a moment, just looking up and staring at it and going, “Wait, is that a baseball?!” Once it landed a few fans ran off in pursuit of it. We all realized pretty quickly it was the first ball to leave the ballpark and it was a pretty cool moment to witness like that. ↩

COUR, JIM. "THE HOUSE THAT GRIFFEY BUILT." Columbian, The (Vancouver, WA), March 30, 1997: 1. ↩

JUDD, RON C.. "IN REAL BALLPARK, SLUGGERS MUST HIT REAL HOME RUNS." THE SEATTLE TIMES, June 19, 1999: C1. ↩

FINNIGAN, BOB. "GRIFFEY UPSET AT BEING USED BY OWNERS." THE SEATTLE TIMES, July 5, 1999: D7. ↩

FINNIGAN, BOB. "GRIFFEY UPSET AT BEING USED BY OWNERS." THE SEATTLE TIMES, July 5, 1999: D7. ↩

https://www.seattletimes.com/sports/mariners/teoscar-hernandezs-struggles-in-seattle-remain-a-mystery-i-couldnt-feel-good/ ↩

staff and wires, from Columbian. "WORKER GETS FIRST 'HIT' AT SAFECO, LOSES JOB." Columbian, The (Vancouver, WA), March 19, 1999: D2. ↩

staff and wires, from Columbian. "WORKER GETS FIRST 'HIT' AT SAFECO, LOSES JOB." Columbian, The (Vancouver, WA), March 19, 1999: D2. ↩

Comments ()