Ernie Tanner, Jimmy Claxton, and the World They Forged

Black baseball history in the Northwest is much more than the Steelheads. Plus, we all need a lot of therapy, baseball fiction, and a solution for baseball's pants problem.

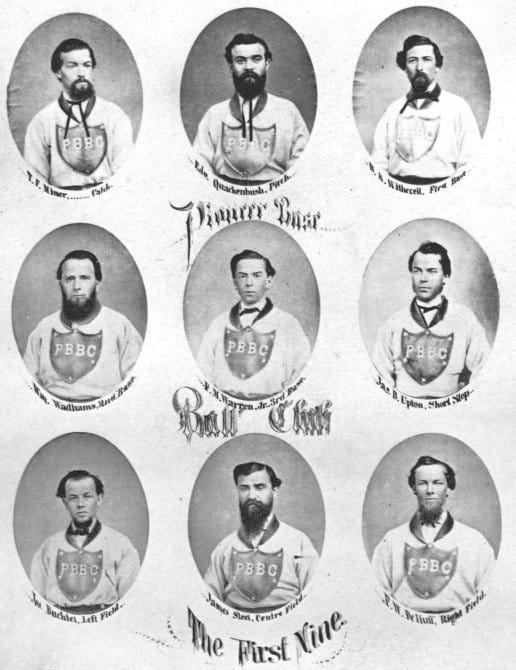

The Mariners first honored the Seattle Steelheads on a Turn Back the Clock Night in 1995. Because of that, baseball fans in the Northwest are aware of the Steelheads, the only fully professional Black baseball team from Seattle. The Steelheads were members of the short-lived West Coast Negro Baseball Association, which played its only season in 1946. There’s a lot that’s appealing about the Steelheads: their professional status, their incredible uniforms, their connection to the Harlem Globetrotters, having a little piece of Negro League history in our backyards.

But Black baseball history in the Northwest is so much richer than three months in the immediate post-war era. What I love about amateur and semi-pro baseball, particularly in the early part of the 20th century, is the way it reflects American culture and history. The players and teams weren’t making a living separate from the realities of life, they were often playing on teams sponsored by their employers or with social organizations. The struggles of the teams reflected the realities of labor and economics, of politics and public life, and the makeup of the teams reflected the racial realities of the times.

The history we hear about the Northwest generally tends to skirt over any sort of racism. You may know that in the first group of settlers in Washington state was a Black man, George Bush, who fled the discriminatory laws in Missouri for Oregon Territory in 1844, only to find the laws in the territory weren’t much better. He and his party moved north to what is now named Bush Prairie. Oregon had Black exclusion laws from the very beginning and much of the state government was infiltrated by the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s. The Klan also held marches in Seattle during this time. Redlining, the practice of excluding Black people from white neighborhoods, was vicious in Seattle and neighborhood demographics in the year 2024 still reflect that legacy.

In between 1844 and 2024, are the lives of real people. The sordid facts of racist history are important to know, but it’s just as important to remember the real people affected by that history. As long as baseball has been played in the Northwest, it has been played by everyone, including the Black population. Today, I want to look at a couple of prominent players who don’t get enough acknowledgment. Ernie Tanner and Jimmy Claxton were incredibly influential on the local baseball scene, and beyond.

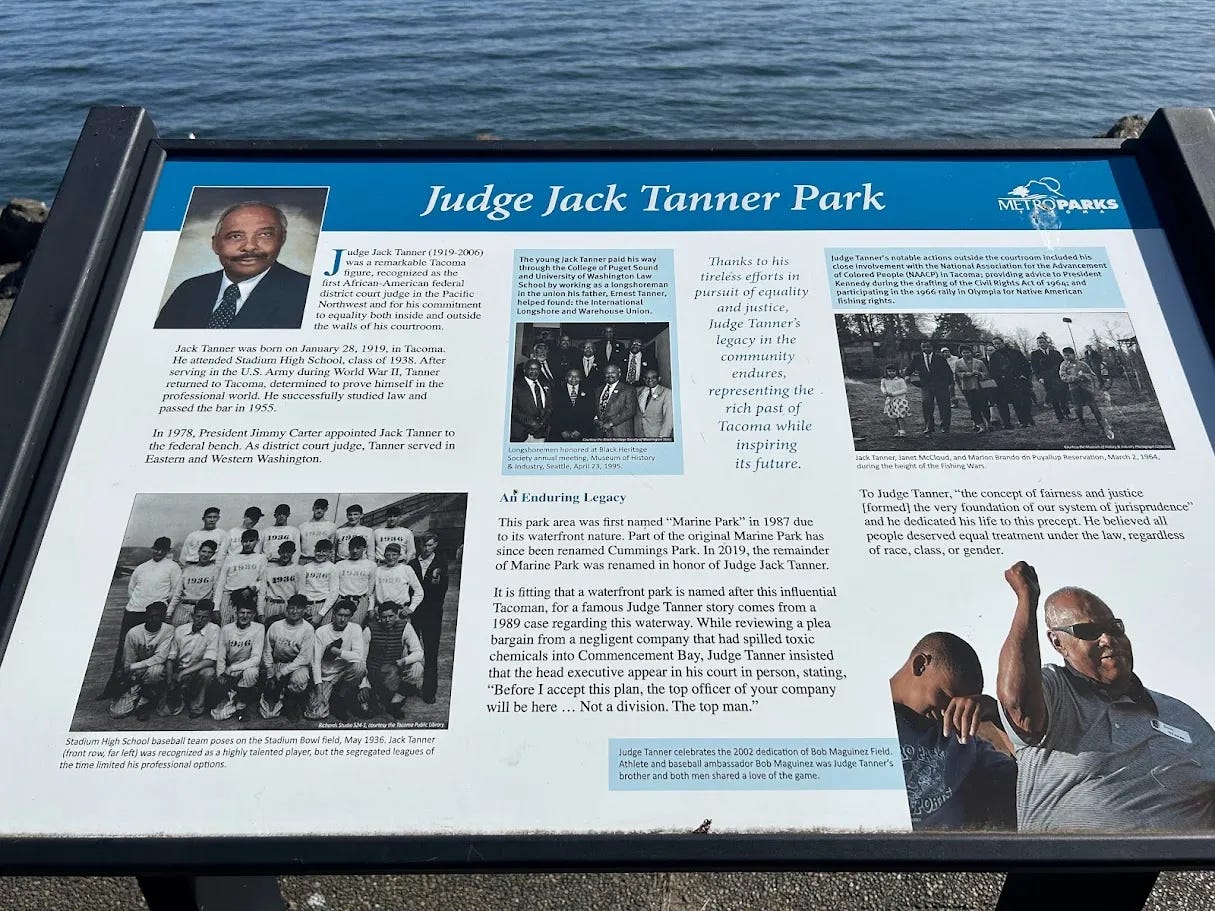

One of the most famous figures in Tacoma is Judge Jack Tanner. In 1978 he became the first Black federal judge in the Northwest. He has an incredible legacy as a lawyer and on the bench and a park on Tacoma’s Ruston Way waterfront is named after him.

Before he embarked upon his legal career, he was a star football and baseball player at Stadium High School. Mentions of him fill Tacoma newspapers during his high school years. The baseball picture of him on the plaque above, appears to show that he was the only Black player on the 1936 Stadium team that won the unofficial (there was no official playoff system in place then) state baseball title.

The plaque asserts that Jack didn’t see a path toward a baseball career. The major and minor leagues were still segregated, but it may be that he simply wanted a different path. Many of the newspaper stories about him also mentioned his father.

30 years before Jack Tanner was a Stadium sports star, his father had also held that title. Then simply called Tacoma High School, Ernie Tanner dominated the high school sports scene as a letterman in football, basketball, track, and baseball. In 1956, a sportswriter asserted that “Tanner undoubtedly is the greatest all-around athlete that Tacoma high schools produced.”1

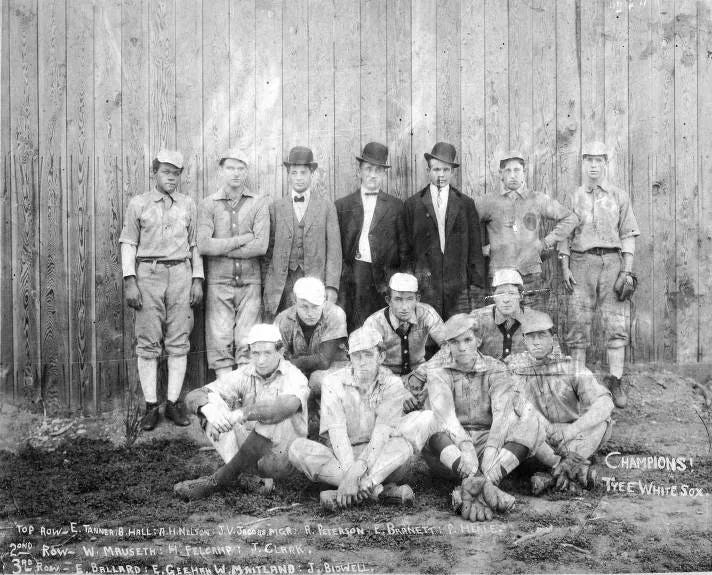

After he graduated he moved on to Whitworth College (then located in North Tacoma) where he became the first collegiate Black football player in the state of Washington. Among his achievements, he scored a touchdown for Whitworth, helping them to a huge upset victory over the University of Oregon in 19082. His college football career did not mean the end of baseball for him. He continued to play on Tacoma’s amateur teams. In 1910 he appears to be the only Black player on the Tyee White Sox, who claimed that year’s City Championship.

Just as the major leagues had a “gentleman’s” agreement to exclude Black players, so too did amateur and semi-pro leagues. In 1915, Tacoma decided to participate in playing for the National Amateur Baseball Championship. What had once been a fairly chaotic organization of teams playing for a city championship, was brought into a highly structured league to determine the team that would represent Tacoma. Although I never ran across any newspaper accounts specifically stating this was the case, it’s easy to read between the lines when the league leaders talked about professionalism and respectability to see that the league intentionally kept out Black players. The Tacoma Daily News didn’t get the memo, and as the teams were signing players for the new city league lamented that managers were overlooking Tanner, writing that he was “one of the best hitters among the local semi-pros.”3

Tanner wasn’t sitting around waiting for a phone call though; he had moved on years before and joined the all-Black Tacoma Little Giants, where he served as both manager and catcher. The Little Giants played white teams, quickly becoming one of the best in the city. In 1912, the Little Giants were playing for the city title. In a game in which the winner would move on to the championship round, the Little Giant’s opponent did not appear and the championship was awarded to another team.4 In 1913, the Little Giants tried to join the Tacoma City Baseball league, even going so far as to contribute money to the fledgling league. But they were not selected to join and were likely purposely kept out because they were a Black team.5

The Little Giants didn’t fold, however. They continued playing independently for another decade, traveling throughout the Northwest to take on other Black teams. Despite being kept out of organized city baseball, the local newspapers were still compelled to report on the Tanner’s baseball team and his prowess on the baseball field. Among his many teammates was a man who would become a lifelong friend, Jimmy Claxton.

*****

Jimmy Claxton played baseball from the age of 13 until his early 60s. He claimed to have played in every state in the contiguous United States except Texas and Maine. It seemed that he had taken on teams in every city in the Northwest.

Claxton was born in British Columbia in 1892. His mother was white and his father was Black; finding a church to marry them was challenging and the couple fled Roslyn, WA, where they had met, finally finding a church in Canada that allowed them to wed. The family moved to Tacoma when Jimmy was a few months old, and following his parent’s divorce at age 10, he moved east with his father to the mining town of Franklin, WA on the western slopes of the Cascades.

Mining work had become a major industry to Black workers at the time. The city of Roslyn, on the side of the mountains, was first populated with Black workers when they were unknowingly recruited to break a miners strike. That tactic was also used in other mining towns, including Franklin. As a result, the Black populations of these town often outnumbered that in larger cities. Jimmy grew up watching his father work in the mines and when he was in high school he decided to leave school and go to work as well. He wasn’t satisfied simply collecting a paycheck, however. He believed that he and other Black workers deserved a say in their working conditions. In 1912, he successfully integrated the United Mine Workers union. It brought an end to using Black workers as strikebreakers and was the beginning of his career in integration.

Although Claxton worked as a miner, his heart was always with baseball. He played on company teams in the Coal League of eastern King County and Central Washington. He was often the only Black player on his team. He also stood out as a left-handed catcher before taking advantage of his strong arm and moving to the pitcher’s mound. After playing on a number of teams around Washington state, he moved down to Oregon with the goal of integrating the Pacific Coast League.

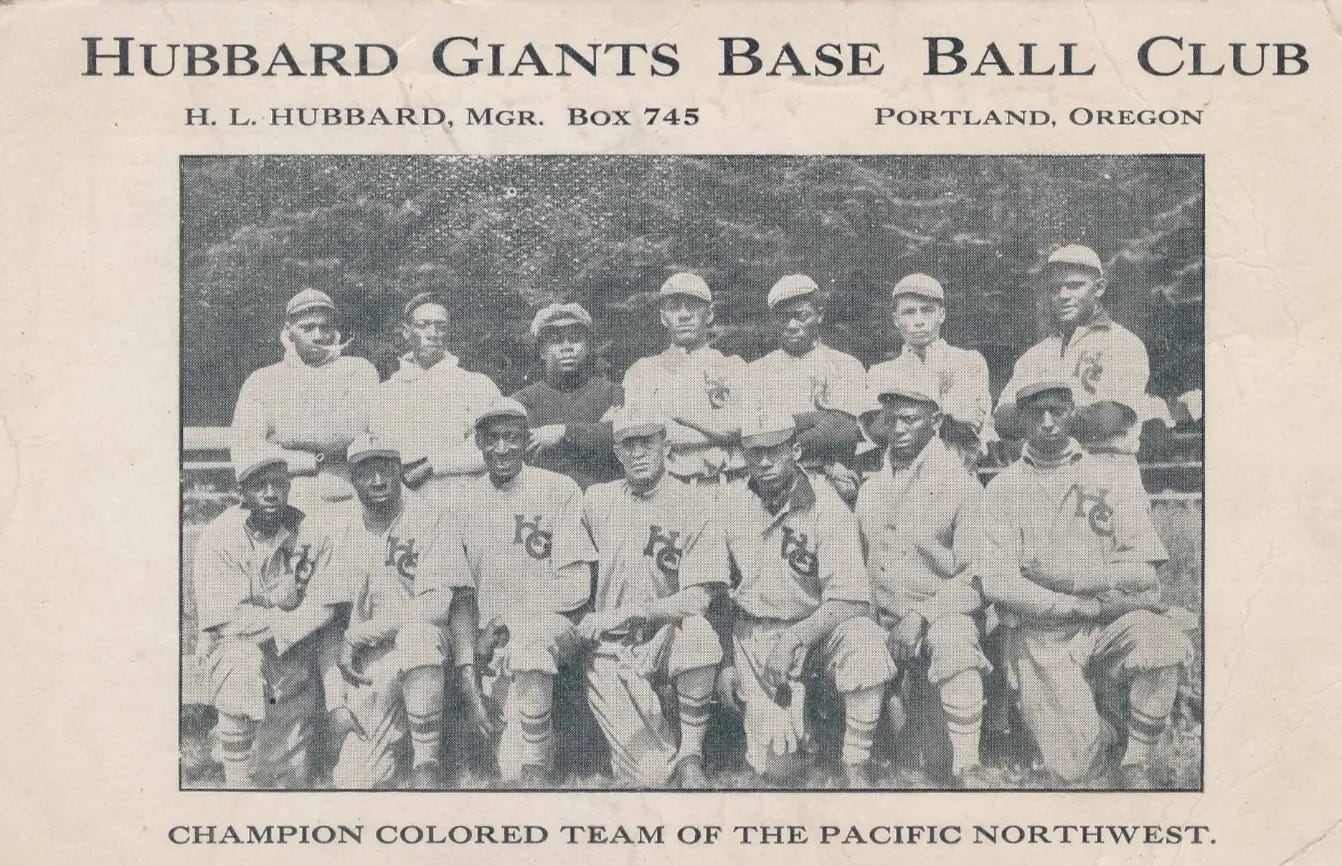

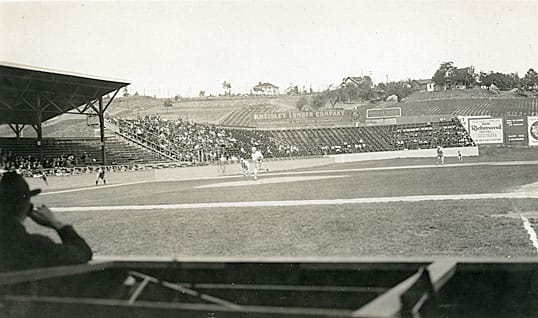

To work his way up, he played on several teams in the area. In 1914 he was a member of Portland’s Hubbard Giants. They claimed to be the best Black team in the Northwest.

After the Hubbard Giants, he integrated the Sellwood Dingbats (!!). At the beginning of 1916, he had plans to do the same with the Gresham Giants. However, Claxton’s presence on the roster led local business owners to pull their financial support and demand that the manager who signed him be fired. When Claxton was released, the manager was rehired and the team was suddenly in the good graces of its financiers.6 The Portland Beavers of the PCL initially expressed interest in using Claxton to integrate the team and the league, but backed away when their annual series with Rube Foster’s Chicago Giants drew condemnation from other PCL owners who believed their white players should not be forced to share a baseball field with Black players.

Claxton moved on, down the coast to Oakland. There he signed with the Oakland Oak Leafs, the top Black team in the Bay Area. The Oak Leafs played against white semi-pro and amateur teams in the area and Claxton thought this was a great opportunity for him to be noticed by white teams. Oakland newspapers certainly took note of Claxton; he was covered well during the early part of the season.

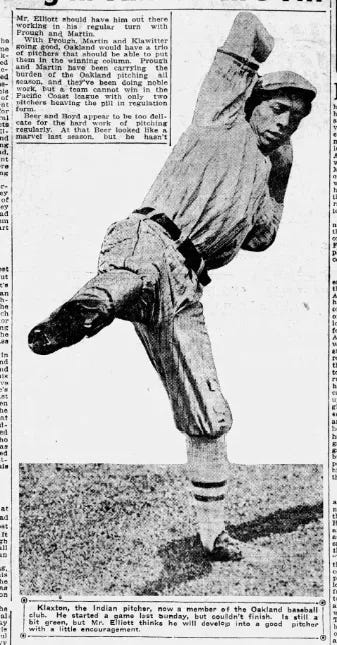

This is why it’s strange that when he was given a tryout with the PCL Oaks, the newspapers described him as “the Indian hurler from the northwest.”7 While white professional leagues agreed to keep out Black players, Native Americans were welcome to play. Claxton claimed indigenous heritage on his father’s side, and the story seems to be that he was introduced to the Oaks that way. Claxton seized a small piece of his heritage and tried to find a way in a side door.

This wasn’t the first time Claxton’s racial classification was in flux. In the book The Integration of the Pacific Coast League, author Amy Essington spends two pages on the various ways Claxton and his siblings had their race classified by census takers.8 At different points, they are listed as white, Black, or mulatto. As Essington points out, the closer they were to whiteness (for example, staying with white relatives) the more likely they were to be classified as white. It’s a prime example of the ways that racial categorization based on observed physical characteristics and the resulting segregation were absurd.

Claxton’s PCL career only last one day. He pitched both games of a doubleheader, the Oaks losing both to the Angels. His performance wasn’t good. The Oakland Tribune wrote:

Claxton, Indian southpaw, received his first touch of Coast league treatment in the a. m. struggle by being driven out of the box by the Angles in the third inning. The youngster was wild and nervous on the rubber and he started his own downfall by walking Koerner in the second inning. McLarry then bunted to the pitcher’s box, whereupon the Indian heaver tossed the pill wide to second and two were on.9

Claxton was pulled from the game in the third with two runners on and no outs. In the second game, he entered in the 9th inning. The box score is unclear on how he pitched, but he was not the last Oaks pitcher in the game. To make matters worse, the Tribune spells his name Claxton (correct) and Klaxton (incorrect) in the same game story.

In Darkhorse: The Jimmy Claxton Story, author Ty Phelan notes:

As a Bay area umpire, Bill Guthrie had previously called at least one game that Claxton pitched for the Oakland Oak Leafs. He knew the young hurler was African American, and efforts to pass him as Native American were futile. His decisions certainly seemed to favor the Angels.10

On May 30th, the Oakland Enquirer ran a picture of Claxton and offered hope for his professional future, writing that Oaks manager Harold “Rowdy” Elliott “thinks he will develop into a good pitcher with a little encouragement.”11

The following day the Oakland Enquirer ran an article that included speculation about what tribe Claxton belonged to, pointing out how dark his skin appeared.12 Shortly thereafter, Claxton was released. He was the last (known) Black player in white organized baseball until Jackie Robinson played for the Montreal Royals 30 years later.

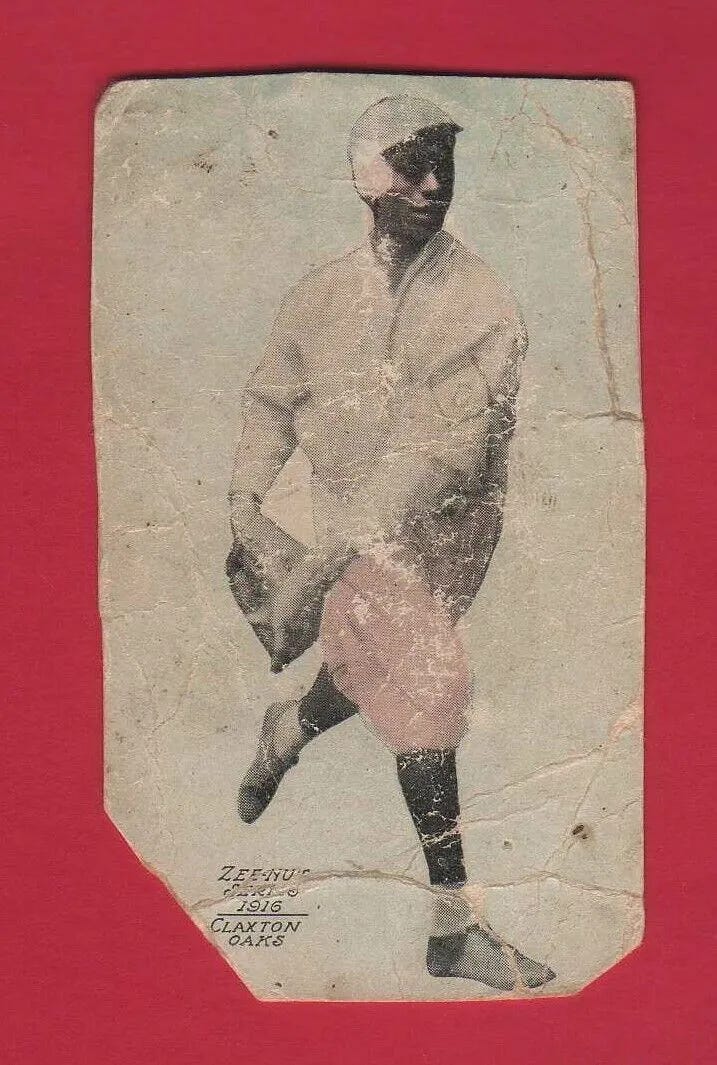

For those of you who love a good piece of baseball trivia, Claxton’s brief time in the PCL leaves a good one. While with the team, the Oaks were photographed for the Zeenut Baseball Cards and Claxton became the first Black player with a baseball card.

After leaving Oakland, Claxton returned to Tacoma and reunited with his friend Ernie Tanner. Tanner got him a job as a longshoreman. In 1918, Tanner joined the International Longshoreman’s Association and became a leader in the union’s efforts. That year he also married Claxton’s sister, Emma. The following year, their first son, Jack, was born.

*****

Claxton moved from town to town, integrating teams in rural areas and joining Black teams in metropolitan cities. He always returned to Tacoma though. There, in 1924, he and Tanner played together on the longshoremen’s entry in the Tacoma Industrial League. Together, they integrated the league, breaking the all-white hold on an important semi-pro league and giving Black workers another piece of the pie.

While Claxton continued focusing on integrating baseball teams, Tanner turned toward his union work. He was the only Black member of the 1934 “Big Strike” committee. This was a massive strike that shut down ports on the West Coast and massively disrupted shipping. After serving during World War II, Jack joined Ernie on the docks, working his way through college, first at the College of Puget Sound, then at the University of Washington Law School.

Ernie Tanner died in 1956. An obituary in the sports section of the News Tribune included a remembrance from a high school teammate:

I am sure if it had not been for the color barrier, Ernie would have made the major leagues long before Jackie Robinson. I think he was a better baseball player than Robinson. He was faster and could hit more. I am confident he would have made any of the National Football league teams. He was the most powerful runner I ever saw.13

*****

Jimmy Claxton reached the Negro League in 1932 at the age of 39 with Pollack’s Cuban Stars and the Washington Pilots in the East-West league. He only played a few games, but it’s enough for him to have a listing on Baseball Reference in the major leagues. He continued playing on teams into his 50s.

His final game was a Tacoma City League Oldtimers game in which he was part of “Possibly the oldest battery seen in a long time anywhere” when he started the game, throwing two innings at the age of 62 to catcher Frank Tobin, 60.

Claxton was awarded the win.14

Further reading and resources: The single best resource on Black baseball in the Northwest is fantastic little book called Sunday Afternoons at Garfield Park: Seattle’s Black Baseball Teams 1911-1951 by Lyle Kenai Wilson. It isn’t in print any more, although you can sometimes find it for sale online. It is available for in-library use at Seattle’s Central Library and in the Tacoma Public Library’s Northwest Room if you find yourself with a free afternoon. It is well worth the read.

The Tacoma Public Library’s Northwest Room has a collection of newspaper clippings about Ernie Tanner: https://northwestroom.tacomalibrary.org/index.php/tacoma-biography-a-z-tanner-ernest

For more on Jimmy Claxton’s incredible life and career, check out Darkhouse: The Jimmy Claxton Story by Ty Phelan. It has tons of information about Black baseball in the Northwest, as well as societal context.

Oh, you’re crazy. Am I? Or am I so sane you just blew your mind?

A couple weeks ago in his Cup of Coffee newsletter Craig Calcaterra went through every MLB team and identified the vibes for each fan base. Of Mariners fans, he wrote:

I feel like M’s fans are in deep need of a lot of therapy. it’s not their fault, though. They’ve dealt with distant corporate ownership for much of the club’s existence during which they were almost made to feel guilty for expecting all that much. And while I’m not quite sure what the current state of satisfaction is with Jerry Dipoto as GM among Seattle fans, the fact that he likes to make a bunch of deals for the sake of making deals with very few of them actually meaning much has conditioned M’s fans not to know what to expect even if they’re going through motions which, superficially, should inspire hope. I don’t intend to compare being a baseball fan to experiencing childhood trauma, but there are at least some vague parallels between people who were brought up by largely well-meaning but uneven and erratic parents and what M’s fans have had to unpack.15

I’ve been saying for years that Mariners ownership needs to pay for therapy for the fanbase after everything we’ve been through. And I’ve had several conversations about how certain criticisms of Dipoto feel distinctly like daddy issues. So, I guess we’re not doing a good job of hiding our issues if an unbiased, outside source is drawing the same conclusion. It is nice to be seen so clearly. It would be weird if we weren’t like this after everything we’ve been through.

Baseball Fiction

Baseball is the most literary sport and lends itself so well to storytelling and symbolism that I’ve always wondered why there isn’t more baseball fiction out there. I think I’ve read most of the major baseball novels: The Natural by Bernard Malamud, Shoeless Joe by W.P. Kinsella, The Great American Novel by Phillip Roth. The general consensus is that the Art of Fielding by Chad Harbach fits in there too. Some recent baseball novels include The Cactus League by Emily Nemens (a Mariners fan!) and The Resisters by Gish Jen. I know there are others out there, but I’ve always felt like there should be more.

So I was delighted earlier this year when I saw a discussion online about a baseball novel I had never come across before, Squeeze Play by Jane Leavy. She is most well-known for her biographies of Mickey Mantle, Sandy Koufax (apparently Koufax agreed to having Leavy write his biography after reading this book), and Babe Ruth. This book is about a woman beat reporter covering the fictional 1989 Washington Senators and is absolutely delightful. And it did something really well that most non-fiction writing can have a hard time with. It captured how awful the humans who play baseball can be, but it reached past that awfulness and pulled out their humanity. It found the heart of the appeal of baseball.

I also loved, as the fan of team with a catch nicknamed “Big Dumper”, that the catcher for the fictional Senators was nicknamed “Rump”.

All that’s great, but I knew this book was a winner after reading the very first line: “You see a lot of penises in my line of work.”

Speaking Of…

The entire world is built around the male gaze and that’s really unfair. So, when I first heard about see-through baseball pants I was like, hey now, let’s not be too hasty in saying this is bad.

Except it is bad. It’s extremely awkwardly bad. There is no gendered gaze that wants that. I feel so terrible for every baseball player who is wearing those. It is incredible that with all the pictures circulating the internet MLB is still claiming the pants are exactly the same as last year. It’s a The Emperor’s New Clothes situation I guess. I feel like this pants situation would work great in a novel about how baseball is reflective of the current state of the country.

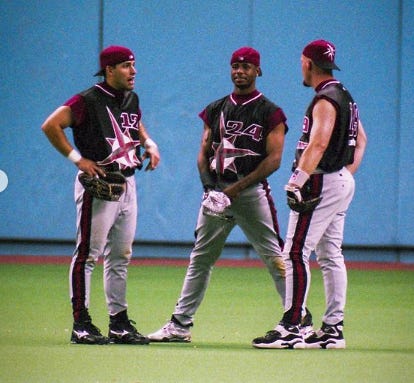

Clearly the pants are cheap and MLB doesn’t care because what’s a little player humiliation when a group of billionaires saves a few bucks. Still, if MLB insists that it needs to save money on clothing the players, there are other options! For example, the Mariners have twice turned the clock ahead and I think we can all agree, not having jersey sleeves is a better idea:

(Looking at the original Turn Ahead the Clock Night, Bobby Ayala blew the save and got the win. The 1990s Mariners, everyone, the source of my childhood trauma and need for therapy.)

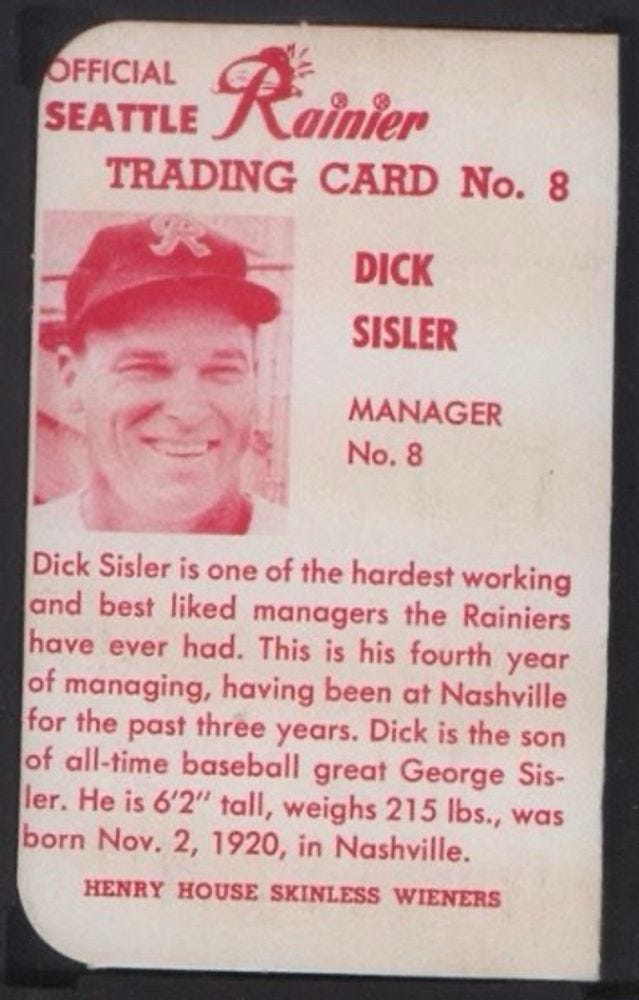

And While We’re Here

Presented without comment, except wait until you read who sponsored this card (courtesy of Matthew Glidden):

Walton, Dan. “Sports-log.” The News Tribune (Tacoma, WA), May 20, 1956, B5. ↩

“Oregon Downed By Whitworth.” Tacoma Daily Ledger (Tacoma, WA), November 8, 1908, 34. ↩

“City League Notes.” The Tacoma Daily News (Tacoma, Washington), March 4, 1915, 11. ↩

“City Title Goes to Gas Co’s Team".” Tacoma Daily Ledger (Tacoma, WA), October 4, 1912, 9. ↩

https://www.tacomalibrary.org/blogs/post/ernest-tanner-labor-longshoremen-and-little-giants/ ↩

Darkhorse: The Jimmy Claxton Story. Ty Phelan, Ellensburg, WA, 2016. ↩

Oakland Enquirer (Oakland, CA), May 24, 1916, 9. ↩

Essington, Amy. “The Integration of the Pacific Coast League.” University of Nebraska Press (Lincoln, NE), 2018. ↩

“Angles Make It 6 Out of 7 With Double Victory.” Oakland Tribune (Oakland, CA), May 29, 1916, 10. ↩

Darkhorse: The Jimmy Claxton Story. Ty Phelan, Ellensburg, WA, 2016. ↩

“Oakland Team Hopes to Get Back in the Running in This Week’s Tilt.” Oakland Enquirer (Oakland, CA), May 30, 1916, 9. ↩

“Oakland Fans Trying to Discover Tribe of Indians That Owns Claxton.” Oakland Enquirer (Oakland, CA), June 1, 1916, 9. ↩

“Sports Log.” The Tacoma News Tribune (Tacoma, Washington), May 20, 1956, B-5. ↩

“City Trounces Valley Vets In Old-Time Tilt.” The News Tribune (Tacoma, WA), August 17, 1954, 12. ↩

https://cupofcoffee.beehiiv.com/p/cup-coffee-february-12-2024?utm_source=cupofcoffee.beehiiv.com&utm_medium=newsletter&utm_campaign=cup-of-coffee-february-12-2024 ↩

Comments ()