A Brief History of Baseball Games Take Too Long

Time, time, time, see what's become of me while we take a field trip away from the Northwest into baseball history at large. Plus, Alyssa Nakken makes history in multiple ways.

As long as there have been humans, we have wrung our hands and argued about and worried for the same things over and over and over again. It’s one of the things that fascinates me about humanity. For all the changes we’ve collectively wrought to the planet there are certain things we just can’t move away from. There was a fantastic recent thread on various social media platforms that documents “A Brief History of We Are Raising a Generation of Wimps”. Every baseball fan is familiar with this sort of complaint; each generation of baseball stars complains that the next doesn’t play the game the right way and isn’t like the more superior players from back in their day.

Baseball history is littered with worries that the game is dying, attendance is too low, gambling will infiltrate and bring it down, people like football more, and so on. One of those constant, cyclical worries is that baseball games are too long. It feels like this is a new, recent complaint. Afterall, it wasn’t until 2012 that the average major league game time remained over three hours. But complaining about game times is nearly as old as the game itself.

With the exception of 1894, and based on the data that is available, the average time for a major league game didn’t reach the two hour mark until 1934. From there, it reached 2:30 for the first time in 1954 and hovered in that neighborhood until the 1980s, when it began to steadily rise, reaching 3 hours for the first time in 2000. There are differences in offense and pitching changes across the eras, and the evolution of baseball has had an affect on the length of the games.

I’ve done some reading in the newspapers about early 20th century games, and it’s not uncommon for the time of game to be mentioned in the stories. Zippy games could wrap up in an hour. When the games were drawn out enough that they approached 2 hours, this was always mentioned along with comments about the fans getting restless in the stands.

The expectation of a sub-2-hour game, and the possibility of a 1-hour game sounds outlandish in the year 2023. To learn how we got here, let’s go on a little journey, beginning a century ago.

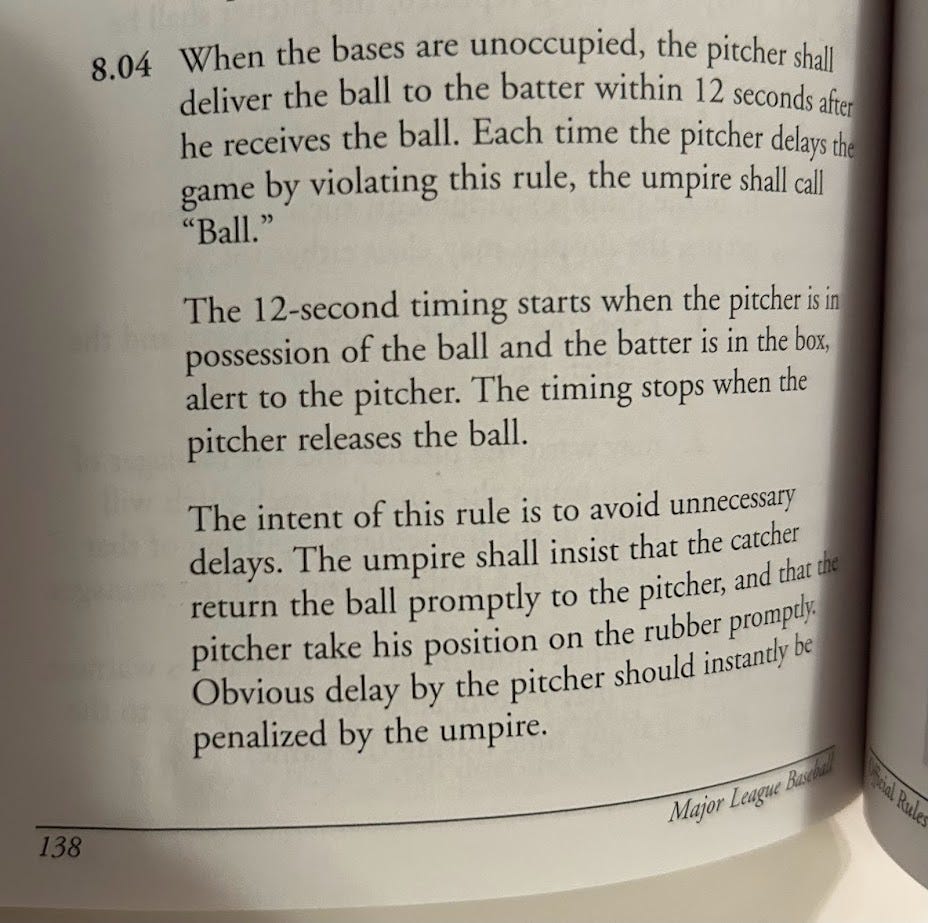

For all the romanticizing about baseball as a game without time, where you can stay forever young if you simply avoid making an out, the idea behind the pitch clock isn’t new. Since 1901, the major league rules have specified that the pitcher must deliver the ball within a set amount of time with the bases empty. Up until 2006, they were given 20 seconds. In 2006, it was amended to 12 seconds. (There was no time restriction with runners on base.)

In November 1924, Thomas J. Hickey, president of the minor league American Association, was convinced that the length of baseball games was a problem and a threat to his league’s coffers. Worrying that fans would stop coming out to games, he said, “Umpires do their best at all times to hurry games but additional incentives are needed to impress upon the players the fact that the public prefers shorter ball games”.1 I don’t have the time stats of his league, but I think we can presume that minor league games weren’t so wildly different from the major leagues that they were playing 4 hour games. The average time of game in the majors that year? 1:54.

A dozen years later, Rogers Hornsby, who famously had a healthy work-life balance with baseball, complained about the livened ball and how long games took:

“They say the fans want more baseball. That’s all right. But why not give them the kind of baseball that keeps them on edge for nine innings? Now you see them start walking out in the fifth inning of the second game of a double-header. They get too much baseball. Games last too long and are too one-sided.2

The average game time in 1936? It jumped to 2 hours and 7 minutes.

The complaints about game times picked up again in the post-war years. This time, they came with a mild backlash. Some writers believed that the complaints about game times were an attack on the National Pastime itself and pushed back. In 1946 (average major league game length 2:08), a newspaper column called Colonel Stoopnagle’s Scrap Book suggested “Abbreviated Baseball for Busy Bozos!”. Abbreviated Baseball was simply a baseball game cut in half played with literally half a baseball on a half-sized diamond. A batter is allowed 1 1/2 strikes and 2 balls. A home run is an out, and only the 1st, 3rd, 6th, and 9th innings are played, although “if a spectator is in a very special hurry, we play the 9th inning first, so he can go home almost as soon as he’s seated.”3

In 1950, the average game length had jumped up to 2:21 and the baseball men were alarmed. In an article that quoted both league presidents, the National League’s Ford Frick blamed it on the pitchers, saying “The reason games are so slow is that present day pitchers are wild and throw a lot of balls. We can’t legislate against that.”4 Both Frick and the American League’s Will Harridge wanted to return to two-hour games.

The hand wringing about the length of baseball games really took off in the 1950s. As the NFL gained more popularity midcentury, for the first time baseball had a competitor for the hearts and minds of the sporting public. Baseball attendance did take a dip in the 1950s, from all-time highs of over 20 million fans in the immediate postwar years down to a low of 14,384,000 in 1953, a number was still higher than any pre-war year. From there, attendance number generally rose, with a few dips here and there. Each time the total numbers dipped, it ignited a round of worry about the demise of baseball. Among the worries? Long games were keeping fans away and new technology was driving some of the changes.

Arthur Daley of The New York Times blamed television for the creeping length of games, writing in 1952:

Pitchers dilly-dally on the mound. Managers dispute umpires on every possible decision for no more discernible reason than to hog the television cameras and put on a show for the videots at home. Notice a manager the next time he gets into an argument. He won’t turn his back on the camera. No, sir. he gives with the profile…A great game is being slowly strangled by such tactics.5

In the mid-1950s the average game time reach 2 1/2 hours. There was a steady stream of newspaper columns, quips, and letters to the editor about how interminably long baseball games took. Despite the fears that baseball was dying, the major leagues added eight new teams during the 1960s, and introduced divisional play and playoffs for the first time. In another round of complaints that will sound familiar to modern fans, the blame was aimed at managers, in addition to umpires, for overthinking their tactics. Hall of Fame pitcher Bob Feller took some of the blame, saying “I was the originator of the three-hour ball game and it’s damn boring…The extra time is the result of over-managing, over-umpiring and over-advising.”6

Game times steadily rose, reaching 2:45 in the mid-1980s. The times continued to rise into the 1990s as baseball faced stiffer competition from rival sports leagues. Again, baseball adherents pushed back against the complaints that games took too long. Take this 1997 Nike commercial for example, one in a series of commercials that ran that year defending baseball from its detractors:

This ad uses old-timey graphics to imbue the idea of baseball as a long, relaxing game with nostalgia. In 1997, the average game lasted 2:56. The real baseball old-timers would have lost their minds at the proposition that this was fine and good.

The average game time continued to rise, until this year when, because of the pitch clock, it plummeted to 2:46. This is down from 3:06 in 2022 and an all-time high of 3:11 in 2021. Over the years baseball has undergone a tremendous amount of change. The game in 2023 is incredibly different than it was in 1924, the year of our first complaint. So, I find it quite amusing that when defending baseball against its modern detractors, much of the blame is layed upon smart phones and video games and our short modern attention spans.

It’s unlikely that the pitch clock ends worries and complaints about game length. It’s just the latest stop on our tour through time.

(For the record though, I do love the pitch clock.)

However, Some Things Do Change

I’m generally going to stay away from commenting on current baseball events in this newsletter. There are plenty of other sources you can go to for that. But this one means something to me, so it’s getting commentary.

Last week, Alyssa Nakken became the first woman to interview for a major league managerial position. She’s been a coach with the San Francisco Giants since 2020 and interviewed to replace Gabe Kapler, who was fired last month. I don’t have high hopes that she’ll get the job; I still remember all the years teams shouted to the world that they were interviewing Kim Ng for a General Manager position before she was finally hired by the Marlins (and recently stepped down because the Marlins are cursed to be run by deeply unserious people).

An interesting note about Nakken though is not just that she’s a woman. She is also pregnant, due with her first child in February. This is significant and symbolic. The specter of pregnancy has been used as an excuse for keeping women out of positions of power and responsibility.

There are many examples of women taking on big jobs while pregnant, or shortly after giving birth, as there are examples of women becoming pregnant while in big jobs. Personally, I always have two equal reactions to these stories. The first is always, hell yeah! We can grow entire humans AND run entire countries! The second reaction is, okay yes, but, phew, pregnancy can really suck. There’s no way to know how it will affect you until you do it. Same with giving birth. And having an infant. It’s all such a wild thing. And in a functional and normal world, all of that would be accommodated and respected in the workplace and society at large.

But we live in this world instead, and it isn’t. So, it’s really awesome to read that the Giants interviewed her knowing all of this. When she announced her pregnancy, she spoke with reporters about her experience with it and said the Giants supported her when she struggled with morning sickness (we really need to rename this because I can attest it’s not just in the morning!). She did not travel with the team on a 10-day road trip in July because she was too sick. When she rejoined the team, accommodations were made for her. She didn’t play catch or stand by first base during batting practice. When she was on the field, she stood behind a screen.

In an interview with Susan Slusser of the San Francisco Chronicle, she talked about the support she received from the organization and of her plans for coaching after the birth of her child, saying “We have coaches having kids and they’re back in three days. I just physically won’t be able to do that.”7

The article by Andrew Baggarly in The Athletic that first reported her interview also mentioned her pregnancy and shared the above quote, adding, “Or can she? Clearly, the Giants’ top decision makers think highly enough of Nakken that they are willing to raise the question.”8

No, she cannot come back in three days! Giving birth to another human is immensely different than being present while someone else gives birth to another human. There is absolutely no way to tell in advance how a birth will go. Even after the easiest birth, a three-day turnaround is utterly incomprehensible. It would be absurd to even suggest that, and I sincerely hope that’s not something anyone in the Giants organization would think is appropriate. Her being out for weeks or months at the beginning of the season would change the way they begin the season. But you know what, so does an ace pitcher blowing out their elbow or a team’s top offensive player breaking their hamate bone. Things happen that change baseball plans out of the blue all the time. There’s no reason that an expected change couldn’t be accommodated and embraced.

As Nakken herself said in the interview with Slusser, “I want to be in this game for a very, very, long time, and this phase is just a small piece of what my entire career could be.”9

Even if she isn’t hired to be the first woman manager in the major leagues, she will be coaching with a newborn. She said she plans to have her husband and baby travel with the team on road trips, so she can embrace motherhood and do her job. With all the societal expectations and pressures of motherhood, that’s a pretty cool trail to blaze.

“Baseball Games Last Too Long, Says Hickey.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, November 20, 1924: 34. ↩

Grayson, Harry. “By Harry Grayson.” Lexington Herald-Leader, July 30, 1936: 8. ↩

“Colonel Stoopnagle’s Scrab Book: Abbreviated Baseball For Busy Bozos.” The San Francisco Examiner, March 10, 1946: 118. ↩

Grimeley, Will. “Changes in Order For Baseball Games Are Too Long.” The Ada Evening News, May 18, 1950: 12. ↩

Daley, Arthur. “Sports of The Times: Study in Slow Motion.” New York Times, August 29, 1952: 19. ↩

“Must Shorten Games—Feller, The Speaker.” The Akron Beacon Journal, June 20, 1967: 19. ↩

Slusser, Susan. "Having her back." San Francisco Chronicle, August 17, 2023: B001. ↩

https://theathletic.com/4964585/2023/10/15/san-francisco-giants-alyssa-nakken-managerial-opening/ ↩

Slusser. “Having her back.”: B001. ↩

Comments ()